![]()

![]()

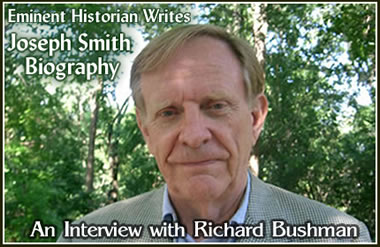

By Maurine Jensen Proctor

Meridian: When you are considering the life of someone like Joseph Smith, who millions revere as a prophet and others take as a fraud, what is the historian’s role?

Richard Bushman:

I think that much of our faith is in certain events in history, and that begins with the creation of the world to all the prophets down through time. What matters to us most is what actually happened – moments when we think God interacted with humankind. To understand the religion that is in those events, we have to return to history.

We’ve become very interested in Joseph and the happenings in his life, and what they tell us about God’s plan for us. We can’t separate our religion from history. A historian has to deal with all the facts around it. My impression is that the Saints truly want to know that story. Of course, it is also the point in which we are attacked, because critics of the church attack us in our history, saying that those things didn’t happen, or we have misconstrued them. It is important in writing about Joseph Smith to tell the story according to the facts.

Yet determining facts is extraordinarily complicated on the simplest matters. People cannot say for sure how many people were in the Mayflower when it landed on the shore or on the Brooklyn when it sailed. One of the chief functions of a historian is to evaluate all the contested sources and arrive at a judgment.

The other critical task is to interpret the facts. No fact stands alone. Everything is interpreted. When we hear a story that dispirits us about the Church, such as the way Jon Krakauer or Fawn Brodie tells the story, it is because they are giving it their own interpretation. We want to tell the story the way we understand it, interpreting and arranging those facts in the way we believe is most accurate and most true.

Meridian: As a believer, how can you avoid writing about Joseph Smith with a bias?

Richard Bushman:

We all have biases and there is no point in pretending that you don’t have a bias. It’s true for everyone and every sophisticated historian admits this. We talk about objectivity as if you could stand aside from yourself and arrive at some totally objective opinion. You can argue with people’s interpretations, but in the final analysis, there is inevitably going to be bias. That being said, the responsibility then shifts from the historian to the readers. They are as vital a part of the process as the historians. They have to judge if the historian’s reading of the events satisfies them. So you must read critically and not be taken in by the notion that the history is simply self-evident.

When you set out to write about Joseph Smith, it is certainly going to be controversial. You know from the beginning of the project that you can’t satisfy everyone. There are people with pre-formed opinions of Joseph Smith who simply won’t agree with my explanation of his life.

The key thing for me is to be as open minded as I can. I don’t try to alter events in a way that will always make Joseph Smith look good. I think doing that destroys your own credibility. What I do try to do is to present events in the way that I truly believe they happened.

I will add this that in writing this book, I was very much aware of the huge philosophical problem, that is – where do ideas come from? I would read and read, get all the source materials in my mind, all there suspended, and then I had to bring those things down into a pattern to define some narrative and some story that holds them all together. These ideas come. The analogy I’ve used is that it is like a man sitting by a campfire in a dark forest and from time to time a figure emerges out of the darkness into the light of the campfire. I have no idea where they came from, but they came. As a Latter-day Saint you hope it is inspiration of the right kind.

Meridian: A volume like this involves thorough and long research. How long have you been working on this project?

Richard Bushman:

I began working on this volume in 1997, but I had written Joseph Smith and The Beginnings of Mormonism in 1984. That took me three or four years.

It’s a huge task to survey the sources. There’s a lot of scholarship that’s gone before, some of which you can rely on its conclusions. For the critical line of the narrative, you have to use the secondary sources to get back to the primary sources. There footnotes would point me to the major primary documents. I had to go back and read those. Fortunately, the vast majority are available online in one way another. Hundreds of original memoirs and journals in their raw form are available and all the papers of Joseph Smith are available too.

There are always items at the edges that you know you haven’t got to, and it’s a little bit unnerving, but I felt if I could cover the 90% at the core and knew what was in them, I could safely make a judgment. People after me will discover new items and add to the story, but I simply couldn’t do all of that myself.

Meridian: What surprised you as you delved into Joseph’s life?

Richard Bushman:

I was surprised by the number of times that Joseph said, “I’ve now finished the work,” He begins saying that in 1830, then again after 1836 after he organized the high council in Zion. It gives the picture of a prophet who was given a charge, he labors intensely, and then he thinks, now. I’ve done my job. It’s a plaintive hope. Then something new would happen to him and he would move to the mode, I have so much I have to teach before it’s all over.

I was surprised how invisible he was. It begins with the Book of Mormon, where the introductory pages say almost nothing about Joseph Smith. He doesn’t mention visions. For a long time I think church members thought of him as an instrument, rather than a powerful, charismatic personality.

Even when Joseph described the restoration he spoke in the passive voice – revelation has been received. His voice is not there. In The Voice of Warning, that great tract written by Parley P. Pratt, he doesn’t mention Joseph Smith until 100 pages into the story. The missionaries are not preaching a new prophet; they are preaching a new truth.

After 1840 he becomes more prominent. His early history is published as a tract in that year. At first, Joseph Smith governed through councils. He immediately began gathering people around him. He wanted joint decisions. He wanted everyone to receive revelation. His inclination is to share the gifts not to dominate the scene.

I was surprised at how tough he was. This seems to be a contradiction to the self-effacing prophet. He didn’t like to be contradicted. He would rebuke his followers if he felt they were the least bit disloyal or trying to go against what he thought was right. Sometimes his temper would flare. He hated contention. It broke his heart and he would plead with people to end adversarial relationships including those with himself.

The other side of his strong will is a yearning for harmony and love at which he was expert. He was spontaneously very affectionate. After an entire day in a council meeting with his brethren he came back, “This has been the happiest day of my life.” He enjoyed being shoulder-to-shoulder and communicating. I think that was important to him because he often thought that people didn’t understand him. He could never quite communicate everything that was in his heart. That yearning to commune made him mentally appealing. You have a person who wore his heart on his sleeve because his emotions were so forthright. That kind of person can be hard to live with but they are also magnetic.

Meridian: What would you ask Joseph if you were to meet him?

Richard Bushman:

I’d ask him if he enjoyed being a prophet. I think he did lots of the time, but it was a heavy burden.

There was a mysterious period from the Kirtland Bank challenges through the extermination order in 1838 where Joseph recedes. There aren’t very many revelations and not much correspondence. The minutes no longer speak of him specificallly, but of the First Presidency. Sidney Rigdon seems to stand forward. He delivers the Salt Sermon and the Fourth of July address in Far West. The records don’t show him actively commanding events. That’s when mistakes were made – when Latter-day Saints tried to expel their enemies from Davies County. The mistake may have been his passivity and letting other less inspired people take the lead for awhile. Not really until the crisis is drawing to a climax does he take over.

It’s that moment where he questioned the Lord. Why are you letting this happen to us? One of his lowest points was in 1833, when the Saints were expelled from Jackson County. He was dumbfounded to have them turned out when he had put so much hope in it. He was distraught. That continued in spades when John Corrill came to him, said he was leaving the Church, and accused him of continually promising things that didn’t work out. It is remarkable that he didn’t crumble in Liberty Jail, but he did have amazing resilience. In some ways I credit him more for that than for anything else – especially on this question of building Zion and gathering the Saints. Partly it’s character, partly he is sustained by heavenly powers. It is a miracle that he held up under it all.

Meridian: How do you evaluate material and sources about Joseph Smith from critics whose goal was to destroy him?

Richard Bushman:

It’s a funny thing about critics because when they are talking about things that happened, they turn the facts in an evil way. In Kirtland, Oliver Cowdery accused Joseph Smith of having an affair with Fanny Algier, but he was married to her. You always have to listen when the critics talk because there may be something there.

For instance, when they accuse him of being a tyrant, it is true from one point of view. He asked people to move and leave their homes and to deed property to the Church. You have to realize there is almost a switch – what is virtuous and self-sacrificing and obedient from one point of view is tyrannical and submissive in another point of view.

Meridian: What did you find yourself admiring about Joseph Smith?

Richard Bushman:

I admire the fact that for so many years, he carried the Church in his own mind. So many of the people who originally followed him, fell away and he had to persist through all of that. He kept developing new leaders and he just never wavered. The Church had to exist primarily in his mind, and he was able to instill the idea of it in all these other minds. Quite early on you could send a Wilford Woodruff on a mission with no contact with headquarters. That capacity to have a vision and then convey it and imbue others with it is remarkable. That is the secret of Mormonism. Every person carries the Church in their own heads.

To that I would add his generosity with spiritual gifts. He wanted to let Oliver Cowdery translate. He wanted everyone to have revelations. It was a democratic spirit to include everyone in this kingdom of glory that he was bringing into existence.

The hardest part for me was reconciling myself to his very stern nature at some points. I don’t like harsh, executive leadership – a personality quirk of my own. I came to realize he had to be tough. If he didn’t have that bull-dog will, he couldn’t have pulled it through.

Meridian: As you began the project, what did you think would be hard about it?

Richard Bushman:

I thought in advance that the intellectually toughest part for me would be the place of women. I recognize that in the early years of the Restoration, women are always present and play critical roles, but they are not involved in the organization of the Church. Then, you get to 184 and the women blossom and are brought forth in the Mormon religion more than any other church at that time. They are brought into the temple rituals. The partnership of men and women become central to salvation. Freemasons didn’t have women in their rituals. No one did. Just in an instant, Joseph gave them this central role. It gave them a key theological role in the Church.

Meridian: How have people responded to the book?.

Those who are not members have responded in quite different ways depending, I think, on their estimation of Joseph Smith. There have been some negative or slighting reviews that dismiss Joseph Smith. There have been a surprising number of positive reviews. Many have felt that they have learned about Joseph Smith. I don’t know how to explain the division. I think that people who come with a pre-formed vision and see him as a fraud, cannot stomach him. Those who see him as bold and marvelous, will be excited by my version of his story.

Meridian: Because we edited a new version of Lucy Mack Smith’s biography of her son, The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, we know the family well. I had some difficulty with your portrayal of Joseph Smith Sr. as a “defeated” man and Lucy as someone whose desire for a home cast them into a bad financial mistake. I don’t see it that way.

Richard Bushman

Years ago when I was working on another book, I decided I would look at rural culture in this period, because I thought I wanted to have that background for writing about Joseph. We have been examining rural society for a long time. Rural America was filled with people who could never get their nose above water, and the problem was debt.

The horrible thing about debt is not that it squeezes your pocketbook, but that it threatens your entire livelihood. That’s what happens to the Smiths over and over. I see them as typical of a huge number of people moving about the edges of American society. I think Joseph Smith was so successful at talking to those people because he had experienced their situation.

The Smiths took their situation personally. They felt they were never respected. Joseph was sensitive about that all through his life. I don’t see it as demeaning at all to say they were poor and suffered.

I don’t see that as a character flaw.

Some critics try to portray Joseph Smith Sr. as a drunk. I don’t think that’s true. The hostile affadivits would have mentioned him in that light if it were. But he did have disappointments enough that he was humiliated by them. It was part of Joseph Sr.’s own disappoint in himself. It’s a human condition. Our deep sorrows weigh upon us.

Meridian: What makes Joseph Smith’s story so compelling?

I think Joseph Smith was a revolutionary theologian. He recast our human understanding of our relationship to God. He found it in the Bible, and I think it can be found there, but it was contrary to all Christian theology at the time. The notion that God looks out and sees all these free intelligences in the universe, takes them under his wing and says, I will teach you to become like me. I think that is a beautiful story and needs much more serious consideration by all Christian theologians.

The classic evangelical objection is that it closes the distance between God and humans and the great drive of Calvinism is to absolve God beyond human context. I honor that, but I think the purpose of religion is to bring us closer to God and bring him into ourselves. There is a difference in theological taste there and I regret that.