Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a series of five articles on the Tower of Babel. To see the previous articles in this series, click here.

Jeff and David Larsen have just completed a highly acclaimed scriptural commentary on the stories of Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. It is available for order on Amazon, the FAIRMormon Bookstore (15% discount), BYU Bookstore, Eborn Books, Benchmark Books, and other select bookstores. See www.templethemes.net for more details.

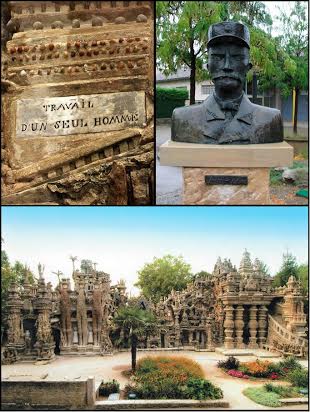

Ferdinand Cheval, 1836-1924: The Ideal Palace of the Postman Cheval (Le Palais Idal du Facteur Cheval), Hautrives, France, 1879-1912

No one in history has wanted to make a name for himself more than Ferdinand Cheval.

Cheval was a postman who lived in Hauterives, France. He began the building shown above in April 1879, claiming “that he had tripped on a stone and was inspired by its shape. He returned to the same spot the next day and started collecting stones. For the next thirty-three years, Cheval picked up stones during his daily mail round and carried them home to build the Palais Idal … He often worked at night, by the light of an oil lamp.”[1] Wrote Cheval: “There was no notion of time anymore when the mail delivery was completed. I could have devoted my free time to hunting, fishing, billiards, or cards – there were plenty of pastimes possible. But I preferred above all the achievement of my Dream. It cost me 4,000 bags of lime and cement and my Monument represents 1,000 cubic meters of stonework – that is to say, 6,000 francs. But because of this, people tell me that my name will go down in history – that’s quite flattering!”[2]

The inscription at top left reads: “Work of one lone man.” Similar inscriptions, along with extracts from poetry and literature, surround the palace: “1879-1912: 10,000 days, 93,000 hours, 33 years of trials-may those more stubborn than me get to work,” This marvel of which the author is proud will be unique in the universe,” “Work is my only glory; honor my only happiness,” “In creating this rock, I wanted to prove what will power could do,” “All that you see here is the work of a rustic.”

Through his work on the palace, Cheval made himself a name. By the end of his life, it had been visited by thousands of people, including art-world luminaries like Andr Breton and Pablo Picasso. After Cheval’s death, a government report declared: “the whole monument is absolutely hideous. It is a pathetic pack of insanities muddled in a boor’s brain.” However in 1969, the French Ministry of Culture declared the palace a cultural landmark. In 1986, Cheval’s image was put on a French postage stamp. The bust of Cheval at top right was commissioned by the people of his town for the fiftieth anniversary of his death. It stands outside the post office – which now, ironically, has been shuttered.

Leon Kass writes the following about the human impulse to make a name for oneself that motivated the project at Babel:[3]

What is this wish “to make us a name“? The verb “to make,” asah, has previously been used only by God, either to announce His own makings or to command Noah’s building of the Ark, or, once, by the narrator to report God’s making of coats of skins. The word “name,” hitherto used in relation to particular names, acquires here a new sense for the first time in Genesis. Adam had named the animals, named himself and the woman as woman and man (‘ishah and ‘ish), and later renamed the woman Eve, honoring her powers as the mother of all life. People give and receive names that are significant (Noah, for example, the first person born after the death of Adam, gets a name meaning both “comfort” and “lament”). Fame and renown are sought, and some men even boast of their deeds (for example, Lamech, who is the poet of his own heroism). But the aspiration to make a name goes beyond the desires to give oneself a name or to gain a name – that is, beyond the longings for fame and glory earned by great success.

To make a name for oneself is, most radically, to “make that which requires a name.” To make a new name for oneself is to remake the meaning of one’s life so that it deserves a new name. To change the meaning of human being is to remake the content and character of human life. The city, fully understood, achieves precisely that. Though technology, through division of labor, through new modes of interdependence and rule, and through laws, customs, and mores, the city radically transforms its inhabitants. At once makers and made, the founders of Babel aspire to nothing less than self-re-creation – through the arts and crafts, customs and mores of their city. The mental construction of a second world through language and the practical reconstruction of the first world through technology together accomplish man’s reconstruction of his own being. The children of man (‘adam) remake themselves and, thus, their name, in every respect taking the place of God ….

In their act of total self-creation, there could be no separate and independent (non-man-made) standard to guide the self-making or by means of which to judge it good. The men, unlike God in His creation, will be unable to see [whether] all that they had done is good. (Indeed, in the story, the Babel builders do not even pause, as God had done, to evaluate their handiwork.) They could, of course, see if the building as built conformed to their own linguistic blueprint, but they could not judge its goodness in any other sense.

In the end, “God will make a name for the one whom He chooses, and,” writes Richard Hess, “that choice is found in the line of Shem, whose name in Hebrew is the word for name.'”[4]

Naming in a Temple Context

Because the Babel story is set in the explicit context of the construction of a temple city, we should not neglect the possibility that the desire of the builders to make a name for themselves has its roots in temple ritual. The importance of naming as it relates to Mesopotamian rites of investiture and Israelite temple ritual is well known:[5]

Although we know few direct details of the Old Babylonian investiture ritual performed at Mari, it is certain that the fourth[6] of the eleven days of the later Babylonian New Year ak?tu festival always included a rehearsal of the creation epic, Enuma Elish (“When on high … “),[7] a story whose theological roots reach back long before the painting of the Investiture Panel and whose principal motifs were carried forward in later texts throughout the Levant.

[8] In its broad outlines, this ritual text is an account of how Marduk achieved preeminence among the gods of the heavenly council through his victorious battles against the goddess Ti’amat and her allies and of the subsequent creation of the earth and of humankind as a prelude to the building of Marduk’s temple in Babylon. The epic ends with the conferral upon Marduk of fifty sacred titles, including the higher god Ea’s own name, accompanied with the declaration, “He is indeed even as I”[9] ….

In Babylonia, as in Jerusalem, “different temple gates had names indicating the blessing received when entering: the gate of grace,’ the gate of salvation,’ the gate of life’ and so on,”[10] as well as signifying “the fitness, through due preparation, which entrants should have in order to pass through [each of] the gates.”[11] In Jerusalem, the final “gate of the Lord, into which the righteous shall enter,”[12] very likely referred to “the innermost temple gate”[13] where those seeking the face of the God of Jacob[14] would find the fulfillment of their temple pilgrimage …

We know nothing directly about the possibility or function of gatekeepers in Old Babylonian rites of investiture. However, it should be remembered that Enuma Elish both “begins and ends with concepts of naming” and that, in this context, “the name, properly understood [by the informed], discloses the significance of the created thing.”[15] If it is reasonable to suppose that the function of sacred names in initiation ritual elsewhere in the ancient Near East might be extended by analogy to Old Babylonian investiture liturgy, we might see in the account of the fifty names given to Marduk at the end of Enuma Elish a description of his procession through the ritual complex in which he took upon himself the personal attributes represented by those names one by one.

Jacob, the Nephites, and the Brother of Jared Receive a New Name

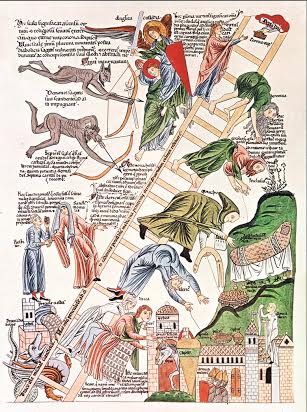

Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Chapter House, Salisbury Cathedral, England, 19th-century restoration of a 13th-century original

Biblical and Book of Mormon accounts tell of individuals and peoples who received a new name.[16] For example, the biblical story of Jacob’s vision of angels ascending and descending on a “ladder” that reaches to heaven[17] resonates with Tower of Babel themes. The Akkadian word b?b-ili means “gate of the god.” In practical terms, this means that “the Babylonian Tower was intended to pave a way for divine entrance into the city.”[18] Nicolas Wyatt[19] sees a likeness to the “ladder”[20] (i.e., stairway, ramp) of Jacob’s dream:

The dream looks suspiciously like a description of a Babylonian ziggurat, in all probability the temple tower in Babylon. This had an external, monumental stairway leading to the top story, which represented heaven, the dwelling-place of the gods.

Jacob will later claim a name with similar meaning to the Akkadian “gate of the god” for the place of his vision: “gate of heaven.”[21] Michael Fishbane notes:[22]

As if to counterpoint the hubris of the tower building on the plain of Shinar,[23] the image of a staged temple-tower, whose “head” also “reaches to heaven,” emerges out of Jacob’s dream-work and humbles him.[24] He does not seek to achieve a name at the nameless place to which he has come on his flight to Aram, but is rather overawed by the divine presence there and extols His name: “Surely Yahweh is in this place,” explains Jacob, “and I did not know it.”[25] Nor does God collude with the pantheon in this text; but rather stands majestically above the divine beings whose “going up and coming down” the tower stairway provides the symbolic link between earth and heaven, and dramatizes the spiritual ascension inherent in the dream vision.[26] From atop this tower stairway promise and hope – not doom and dispersal – now unfold.[27] So as to commemorate and concretize this moment, Jacob, upon awakening, externalizes his dream imagery and erects a pillar whose “head” he anoints with oil: For indeed this place was for him a sacred center, a “cosmic mountain” linking heaven and earth.[28] It was, as he says, a Beth-el, a “house of God” and a “gateway to heaven.”[29] And should he return from his journey in safety, Jacob also vows to recommemorate this pillar and transform it into a “House of Elohim.”[30]

Later Jacob “wrestled (or embraced, as this may also be understood)” an angel who, after a series of questions and answers in a place that Jacob named Peniel (Hebrew “face of God”), gave him a new name.[31]

“[37] The caption on the ladder bears a message of encouragement, proclaiming that all those who have fallen will have the opportunity, through sincere penitence, to begin their climb anew.[38]

A Nephite incident that associates a tower with the giving of a name is found in the Book of Mormon story of King Benjamin’s speech. In reference to Benjamin’s declaration that he “will give this people a name,”[39] Brant Gardner[40] notes that this “new naming is clearly tied to religious principles … In that culture, reality was defined through religion, and the validation of a political reality was the leader’s persuasive claim or demonstration of Yahweh’s sanction.” Catherine Thomas goes further in her interpretation, explaining:[41]

Perhaps this was the first time among all the people brought out from the land of Jerusalem that a king and priest – in the tradition of Adam, Enoch, and Melchizedek – had succeeded in bringing his people to this point of transformation: he had caused them as a community actually to receive the name of Christ.

But what does it mean to receive the name of Christ? We remember that when we take the sacrament, we signify not that we have fully taken the name, but that we are willing to take the name.[42] Elder Dallin Oaks emphasized the word “willingness,” pointing to a future consummation ….[43] In connection with being born again, Benjamin’s people may have received something of a temple endowment.

Catherine Thomas likewise saw “something of a temple endowment” in the experience of the brother of Jared to whom the Lord showed Himself at the “cloud-veil.”[44] But first, like Moses,[45] he was required to reject the counterfeit priesthood of the Babylonians and undergo testing. About Shelem, the place where the brother of Jared received his vision, Nibley explains: “The original word of Shelem, Shalom, means peace,’ but it originally meant safe’ (safety, security) because it was a high place. The Shelem was a high place. It’s still the word for ladder: silma, selma, a sullam in Arabic.”[46]

Seeking the Blessings of Enoch’s People

Donaldson, Rogers, and Seely read the significance of the naming motif in the story of the Tower of Babel in a temple context as follows:[47]

First, the impetus in building this temple was to make themselves a name. In other words, … they [wanted to] build a temple to receive the name of God without making eternal covenants.[48] Second, they wanted to build this tower-temple so they would not be “scattered.”[49] Latter-day revelation ties the temple’s sealing power to preventing the earth from being wasted at the second coming.[50] One meaning of the word “wasted” in Joseph Smith’s day was “destroyed by scattering.”[51] … [The Babylonians] were building their own temple, their gate to heaven, without divine approval or priesthood keys ….

The narrative begun by Genesis ends in 2 Kings 25, in which the children of Israel found themselves – because they broke the covenant – back in Babylon where the story began. Their breaking of the covenant resulted in their exile from Jerusalem (Zion) to Babylon … In the latter days, the Lord once again has called us out of the world: we have been instructed to “go … out from Babylon”[52] to build Zion.

The city of Enoch had been translated[53] before the Flood. However, after the Flood Melchizedek led a righteous community who “sought for the city of Enoch” and “obtained heaven.”[54] This scripture brings to mind the only remark of any length that has been attributed to the Prophet Joseph Smith on the subject of the Tower of Babel:[55]

Now in the days of Noah there was a man [with] the name of Nimrod … After the Flood, God commanded the people to spread over the earth, but they would not, and stayed and stayed upon the high land for fear of another deluge. But Nimrod rose up and said he could withstand God. He said, “Come, let us build a tower here that the water can rise. And I will go up and fight this God.” This is the account Josephus tells us.[56] But God confounded their language and they were obliged to scatter abroad over the land ….

Now I will tell the designs of building the tower of Babel. It was designed to go to the city of Enoch, for the veil was not yet so thick that it hid it from their sight. So they concluded to go to the city of Enoch, for God gave him place above this impure Earth, for he could breathe a pure air. And he and his city were taken, for God provided a better place for him – for they were pure in heart. For it is the pure in heart that causes Zion to be. And the time will come again to meet, that Enoch and his city will come again to meet our city, and his people our people.[57] And the air will be pure and the Lord will be in our midst forever.

Whether or not this sermon is remembered correctly in every detail, the idea that the builders of Babel were seeking to obtain the blessings of those who had been translated with the city of Enoch is significant in light of the previous discussion of the Tower of Babel as a counterfeit temple. From the perspective of earthly and heavenly temple ordinances, the idea that Melchizedek’s people “obtained heaven”[58] in their quest for the city of Enoch means that they “came by the Gospel into God’s presence,”[59] i.e., that they obtained “the blessings of the Second Comforter.”[60] In addition to the possibility of divine tutorial with the Father and the Son that is typically associated with the Second Comforter,[61] the blessings of the Second Comforter include the privilege of communion with other mortals who have been sanctified, i.e., to come “unto mount Sion, and unto the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to an innumerable company of angels, To the general assembly and church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, and to God the Judge of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect, and to Jesus the mediator of the new covenant.

“[62]

The Tower of Babel and the “Great and Spacious Building”

From the previous discussion the relationship between the Tower of Babel of Genesis 11 and the “great and spacious building” that “stood as it were in the air, high above the earth” of Lehi and Nephi’s vision[63] is made clear: they are one and the same. Indeed, Ellen van Wolde points out that the Hebrew term for “heaven” in Genesis 11:4 “can also mean air, and the word is frequently used in the Hebrew Bible in connection with impressive buildings such as fortresses or towers, as in Deuteronomy 1:28 and 9:1, which speak of great cities and fortresses in the air.'”[64] Nephi described the inhabitants of the building as “the world and the wisdom thereof” and the building itself as “vain imaginations” and “the pride of the world.”[65] Like the Tower of Babel, “it fell, and the fall thereof was exceedingly great.”[66]

Noting that the Book of Mormon was written “for our day,” John Mansfield, with tongue in cheek, has been keeping his eye on the Hamburg Elbe Philharmonic Hall as a possible successor to the “great and spacious building” described in 1 Nephi:

1 Nephi 8:19: “And I beheld a rod or iron, and it extended along the bank of the river.”

Hamburg has been redeveloping part of its port on the Elbe [River] as a new quarter called HafenCity.

1 Nephi 8:26: “And I also cast my eyes round about, and beheld, on the other side of the river of water, a great and spacious building.”

“In the middle of the flow of the river Elbe on approximately 1,700 reinforced concrete piles a building complex is emerging, which, in addition to three concert halls, will encompass a hotel, 45 private apartments and the publicly accessible Plaza. The … world-class concert hall [has] a height of 50 meters with seating for 2,150.”

1 Nephi 8:26-27: “And it stood as it were in the air, high above the earth. And it was filled with people both old and young, both male and female; and their manner of dress was exceedingly fine.”

“At a height of 37 meters visitors will be treated to a unique 360 panoramic view of the city. Measuring some 4,000 square meters the Plaza will be almost as big as the one in front of the City Town Hall and will be an ideal place for Hamburg’s citizens and tourists, concert-goers and hotel guests to stroll.”

If nothing else, the building’s budget is “great and spacious.” Reputed as Germany’s most expensive cultural project, the cost of the Hamburg Elbe Philharmonic Hall is reckoned at almost 800 million euros, ten times more expensive than the estimate of 77 million euros proffered by the mayor in 2005.[67]

Click here to see the References

Endnotes

[1] Ferdinand Cheval, Ferdinand Cheval.

[2] J.-P. Jouve et al., Palais Idal, p. 293.

[3] L. R. Kass, Wisdom, pp. 219, 230-231, 234.

[4] R. S. Hess, Israelite Religions, pp. 177-178, emphasis added.

[5] J. M. Bradshaw et al., Investiture Panel, pp. 11, 21-22.

[6] J. A. Black, New Year, p. 43.

[7] S. Dalley, Epic.

[8] K. L. Sparks, Ancient Texts, p. 167.

[9] E. A. Speiser, Creation Epic, 72 (7:140).

[10] S. Mowinckel, Psalms, 1:181 n. 191.

[11] J. H. Eaton, Psalms Commentary, Psalm 118:19-22, p. 405. See also Psalm 24:3-4.

[12] Psalm 118:20.

[13] S. Mowinckel, Psalms, 1:180.

[14] Cf. Psalm 24:6.

[15] B. R. Foster, Before, p. 437.

[16] In this case, the god is Marduk.

[17] Genesis 28:12.

[18] L. R. Kass, Wisdom, p. 229. According to the Chinese Shujing, the motivation for the god’s opponent to damage to the pillar that connected heaven and earth at the time of the Flood was to “break the communication between earth and heaven so that there was no descending or ascending” (J. S. Major, Heaven, p. 26. See also K.-c. Chang, Eve, pp. 70-71; J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Endnote E-207, p. 755).

[19] N. Wyatt, Myths of Power, p. 74. A. LaCocque, Captivity of Innocence, p. 54 notes that unlike the Tower story, it is God that takes the initiative in the story of Jacob (cf. P. M. Sherman, Babel’s Tower, pp. 57-58).

[20] Genesis 28:12.

[21] Genesis 28:17.

[22] M. A. Fishbane, Biblical Text, p. 113.

[23] Genesis 11:1-9.

[24] Genesis 28:12.

[25] Genesis 28:16.

[26] For more on this figure, see the caption of J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure 5-13, p. 351.

[27] Genesis 28:13-15.

[28] Genesis 28:18.

[29] Genesis 28:17.

[30] Genesis 28:20-22.

[31] See B. H. Porter et al., Names, pp. 506-507.

[32] R. Gunon, Symboles, pp. 336-339; J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 7 April 1844, pp. 346-348, 354; M. C. Thomas, Hebrews; M. C. Thomas, Brother of Jared; N. M. Sarna, Mists, p. 82. See also J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figures 1-2 and 1-3, p. 34 and Commentary 1:1-c, p. 43.

[33] M. G. Romney, Temples, pp. 239-240. See H. W. Nibley, Sacred, pp. 579-581.

[34] J.L. Carroll, Reconciliation, p.95 n.18; J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 21 May 1843, p. 305. Joseph Smith used the ladder to represent the process of exaltation: “When you climb up a ladder, you must begin at the bottom, and ascend step by step, until you arrive at the top; and so it is with the principles of the Gospel-you must begin with the first, and go on until you learn all the principles of exaltation” (ibid.

, 7 April 1844, p. 348).

[35] See 2 Peter 1:10.

[36] Cf. J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Commentary 1:25-c, p. 60 and Endnote 1-22, p. 79.

[37] D. Q. Cannon et al., Far West, 25 October 1831, p. 23; J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 25 October 1831, p. 9. Cf. 2 Peter 1:5-11, Moroni 8:25-26.

[38] R. Green et al., Hortus, 2:352-353.

[39] Mosiah 1:11.

[40] B. A. Gardner, Second Witness, 3:108. See also ibid., 3:183-188.

[41] M. C. Thomas, Benjamin, pp. 290-292.

[42] See Moroni 4:3; D&C 20:77. Compare Mosiah 5:5.

[43] D. H. Oaks, Taking Upon Us, p. 81.

[44] M. C. Thomas, Brother of Jared, p. 389.

[45] See J. M. Bradshaw, Moses Temple Themes, The Vision of Moses as a Heavenly Ascent (with D. J. Larsen), pp. 23-50. See also J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 32-81, 694-696.

[46] H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, 16, p. 196. Cf. M. C. Thomas, Brother of Jared, p. 391.

[47] L. Donaldson et al., Building, pp. 60-61.

[48] John S. Thompson sees the confounded language of Babel as pertaining to corrupted temple ordinances: “the language of this false temple was confounded by God and stands in contrast to the preserved language of … true priesthood and temple worship” (J. S. Thompson, Context, pp. 160-161).

[49] Genesis 11:4.

[50] See D&C 2:3.

[51] N. Webster, Dictionary, s. v. “waste,” v. t.: “2. To cause to be lost; to destroy by scattering or by injury.”

[52] D&C 133:5. Babylon is also used elsewhere in the Doctrine and Covenants as a symbol of wickedness, the antithesis to Zion (D&C 1:16; 35:11; 64:24; 86:3; 133:7, 14). For an overview of Babylon in the Old Testament, see P. M. Sherman, Babel’s Tower, pp. 78-83.

[53] See Genesis 5:23-24; Moses 7:21-23.

[54] JST Genesis 14:33-34. Cf. Moses 7:27: “many … were caught up by the powers of heaven into Zion.”

[55] E. England, Laub, p. 175, retrospectively reporting a sermon that Laub dated to 13 April 1843, spelling, grammar, and punctuation modernized. The only other account of a speech by Joseph Smith on that day is “entirely different in subject matter than the one reported by Laub” (ibid., p. 173 n. 24).

[56] See F. Josephus, Antiquities, 1:4:3, p. 30. Note that the Prophet is not claiming that he has received specific revelation regarding the story of Nimrod, but is only summarizing details that are found in the account of Josephus. In 1835, Oliver Cowdery also quoted from Josephus’ account (O. Cowdery, Mummies).

[57] See Moses 7:63.

[58] JST Genesis 14:34. See S. H. Faulring et al., Original Manuscripts, pp. 127-128, 641-642.

[59] H. L. Andrus, Doctrinal (Rev.), p. 252.

[60] H. L. Andrus, Doctrines, p. 52. See H. L. Andrus, Perfection, pp. 366-400; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 73-79.

[61] J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 73-74.

[62] Hebrews 12:22-24. Compare D&C 107:18-19.

[63] 1 Nephi 8:26. See also 1 Nephi 8:31; 11:36; 12:18.

[64] E. van Wolde, Words, p. 92. This reading of the account obviates the need for more elaborate explanations of Nephi’s terminology. For example, it is sometimes assumed, erroneously, that the building hovered above the earth. For example: “[The building] is apparently detached from the world’ because the large and spacious field in which Lehi stands is directly connected to celestialization (the Tree); and the building, though visible to and interactive with those in the field, has no true place in the world of the Tree” (B. A. Gardner, Second Witness, 1:178). See also S. K. Brown, New Light, p. 68, cited in B. A. Gardner, Second Witness, 1:178, for a description of the “so-called sky-scraper architecture” of ancient south Arabia that may have contributed to the imagery of Lehi’s dream.

[65] See 1 Nephi 11:35-36; 1 Nephi 12:18.

[66] 1 Nephi 11:36. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Documentary History, August 1832, 1:283, 13 August 1843, 5:530.

[67] M. Klemm, Hamburg: Elbphilharmonie.