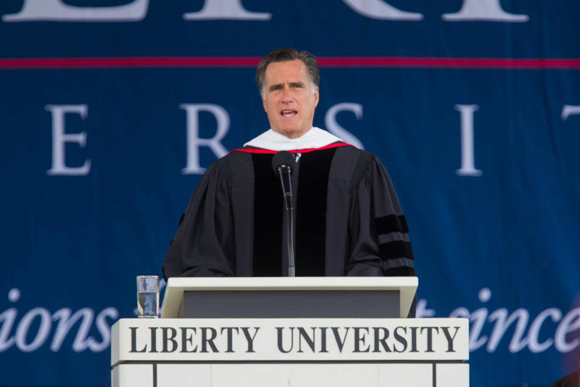

Governor Mitt Romney addresses the Liberty University’s Commencement on Saturday, May 12, 2012. (Photo by Joel Coleman, Source: Liberty University Facebook page.

Governor Mitt Romney addresses the Liberty University’s Commencement on Saturday, May 12, 2012. (Photo by Joel Coleman, Source: Liberty University Facebook page.

A new study (link: PDF) released by the Brookings Institute flies in the face of everything we’ve been hearing this election season about how Mitt Romney’s religion will be a major turn-off for some voters and damage his election prospects.

Brookings fellow Matthew M. Chingos and University of Mississippi assistant professor Michael Henderson argue “that the question of whether Romney’s religion will hurt his electoral prospects is long on speculation and short on evidence.”

A new online survey to 2,084 respondents, approximately 16% of whom were white evangelical Christians, revealed a surprise, suggesting “that concerns over Mitt Romney’s “religion problem” have been overblown and quite possibly miss a compelling counter-narrative. Romney’s religion does not seem to reduce his support among white evangelicals. Even priming these prospective voters to think about differences between their own faith and the Republican nominee’s does not drive a wedge between them.”

Background

It is certainly true, they note, that “decades of polling has shown that Mormon candidates face steep obstacles in the American electorate.” In Gallup surveys going back to 1967, about one in five Americans say they would not vote for a generally well-qualified nominee from their party who happened to be a Mormon. In the 2011 survey, that is the third highest level of opposition, behind only that toward an atheist candidate (49%) and a gay or lesbian candidate (32%).

Even as Romney’s insurmountable lead in convention delegates makes him the presumptive Republican candidate, the authors acknowledge that he has struggled among white Evangelical voters. They say, “Pundits regularly attribute these struggles to a religion problem’ rather than to other sources of disagreement with the candidate. This claim is rooted in the fact that many evangelicals-a staple of the Republican electoral coalition-skeptically regard Mormons as non-Christians.”

They also note, “Mitt Romney did in fact struggle among evangelical Christians during Republican primary voting this spring. According to exit polls, Romney did worse among evangelicals than among non-evangelicals in all but two states, 10 often by double digits. In most states, he lost evangelical Christians either to Rick Santorum or Newt Gingrich, including in many of the states where he won among primary voters overall. In Ohio, for example, Romney eked out a narrow victory despite losing the evangelical vote by seventeen points. Things were worse in the south, a region with especially high shares of evangelical Christians. Romney lost evangelical Christians by 35 points in Louisiana, 33 points in Georgia, 24 points in South Carolina, and 16 points in Tennessee, carrying none of these states.”

Of course, these election results fueled speculation about anti-Mormon bigotry among evangelical voters, still “these supposedly anti-Romney voters are among the least supportive of the president. Only one in four white, evangelical Christians has favorable opinions of Obama. Indeed, among Republicans who do not think of Mormons as Christians-that is, the subgroup believed most predisposed against Romney-fully 92% have unfavorable opinions of Barack Obama.”

The writers suggest that the evangelical Christian reticence to back Romney may have little to do with his religion, but that 44% of them see Romney as “not conservative enough” which may have impacted their decision. Also, decades of election studies indicate that most partisans who initially hesitate about a candidate set aside their differences and develop more favorable impressions over the course of a campaign.

Most Americans do not yet know much about Romney’s religion, but those numbers are increasing from 39% in November of last year to 48% this March. As the campaign fills the informational void, that number will grow.

Polls about reticence to vote for a Mormon for president shed only some light on the topic, but have not tried to account for the increase in information about Mormonism that voters will be exposed to over the course of the general election campaign.

The authors note that the New York Times alone has published articles in the last four months on Mormon history, policy positions and even cuisine (hello funeral potatoes).

So Chingos and Henderson designed their study to seek additional information and designed it as a survey experiment. They describe it, “After respondents were asked to provide background information, they were randomly assigned to receive one of four possible short informational prompts about Mitt Romney.

“The first prompt simply said that Romney was seeking the Republican nomination for president. The second prompt added a phrase indicating that Romney is a Mormon. The remaining prompts also identified Romney as a Mormon but added further details about the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

“The third prompt emphasized a similarity between Mormon doctrine and traditional Christian doctrine, specifically that The Mormon Church believes that Jesus Christ is the son of God and the Bible is the word of God.’ The fourth prompt emphasized differences between Mormons and traditional Christian teachings: In addition to accepting the Bible as the word of God, the Mormon Church also believes that the Book of Mormon is the word of God. The Mormon Church believes the Book of Mormon was written on golden plates by ancient inhabitants of America whom Jesus Christ visited shortly after his resurrection. The Church also believes that the book was later discovered in 1823 when Joseph Smith found it buried in upstate New York.’

“These variations in question wording were designed to test not only if information about Romney’s religion matters but also whether the effect of this information depends on the extent to which it activates stereotypes about similarities or differences between Mormon beliefs and traditional Christianity.”

The result? The study’s authors stated, “We find little evidence that any of the information prompts about Romney had more than a trivial effect on his electoral prospects. what they were told about Romney’s religion. Respondents in general-and white evangelicals in particular-were just as likely to support Romney regardless of what they were told about Romney’s religion.

This non-effect on their support of Romney was just as true whether the prompt emphasized differences or similarities between Mormons and traditional Christians.

Does this mean that information about Romney’s religion does not matter at all? No. They said, “This information does matter, just not in the way that election pundits have speculated. When respondents are broken out by their own ideology, interesting patterns emerge.”

Among conservatives, it increases his support by a considerable 19%. Among white evangelicals, the group that we hear most often has prejudices against Romney, mentioning Romney’s religion has an effect of 20% increase in support..

In contrast, information about Romney’s religion has no impact on political liberals in the sample.

The authors say these results should not be taken as definitive, because they are not based on a nationally representative sample, but this study may suggest that Mitt’s religion problem may not be a problem after all.