![]()

Ziggurats: Temple Platforms of Ancient Mesopotamia

By Daniel C. Peterson and William J. Hamblin

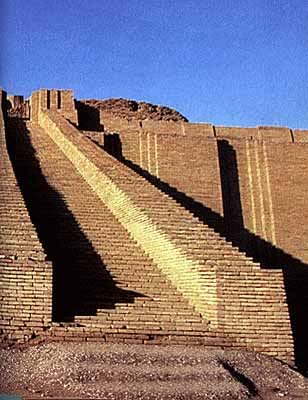

Most religions have attempted to build their sanctuaries on prominent heights. Since no such natural heights were available in the flat flood plains of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), ancient priests and kings determined to build ziggurats (Akkadian ziqqurratu), square or rectangular artificial stepped temple platforms. Functionally, temples were placed on raised platforms to give them prominence over other buildings in a city, and to allow more people to watch the services performed at the temple. Symbolically, however, the ziggurat represents the cosmic mountain on which the gods dwell. The priest’s ascent up the stairway to the temple at the top of the ziggurat represents the ascent to heaven. The great ziggurat at Khorsabad, for example, had seven different stages; each was painted a different color and represented the five known planets, the moon, and the sun.

Ziggurat of Ur-nammu

Although the specific architectural details of ziggurats differ, they all exhibit a similar overall structure. A courtyard surrounded by a sacred enclosure wall-as large as 500 yards square-generally encompassed the ziggurat, creating a ritual plaza for religious ceremonies. Ziggurat complexes often included storehouses, residences for priests and kings, and altars for sacrifice. The huge stepped temple mound-often as long as a football field and generally oriented to the cardinal directions-occupied a prominent place in the courtyard. Ascent of the platforms was often restricted to the priests, and was achieved by climbing vast stairways, some stretching out perpendicular to the platform, with others attached to the walls or spiraling around the platform. The top of the ziggurat was crowned by a temple containing the statue of the god, and representing his or her home. Ziggurats thus provided the link between heaven and earth, allowing humans to ascend, ritually, into the presence of God. (In this regard, Jacob’s vision of the “ladder” or, better, “stairway” into heaven [Gen. 28:10-22] matches the symbolism of the ziggurat.) In Babylon, the largest ziggurat was the Etemenanki (“the house that is the foundation of heaven and earth”), with a square base almost 100 yards on each side. Priests and artisans of Mesopotamia provided their temple and ziggurat complexes with fantastic ornamentation. Twenty-two tons of gold were said to have been used in the ornamentation of the temple of Marduk alone.

Although the building of ziggurats declined following Alexander’s conquest of Mesopotamia, the significance of these temple complexes lived on in the religious imagination for the next two thousand years. Berosus, a Babylonian scholar of the third century B.C., described the Hanging Gardens of Babylon as one of the wonders of the world. He claimed the Hanging Gardens were a type of pleasure palace and garden built by king Nebuchadnezzar for his wife Amuita; the gardens were probably part of a ziggurat complex, intended to represent the celestial garden of the gods which surrounds the mountain on which the gods dwell.

Building temples on raised platforms is a widespread phenomenon in world religious architecture. Functionally and architecturally, however, the closest parallels to the Mesopotamian ziggurat come from the stepped temple mounds of pre-Columbian America. In Mesoamerica, these are most strikingly preserved at the temples of the Maya and Aztecs, but the phenomenon dates back at least to the late second millennium B.C. (as found in Olmec examples at La Venta and San Lorenzo).

When the Arabs conquered Mesopotamia in the seventh century A.D., the crumbling, abandoned ruins of the ziggurats may have been the architectural inspiration for the building of the great minaret of Samarra (near Baghdad) in the ninth century:

This huge tapering tower is surrounded by an outside spiral corkscrew staircase to the top. Seeing this minaret, medieval Europeans mistook it for the biblical Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1-9), and as such it lent its form to medieval and Renaissance representations of the Tower, as in the famous Tower of Babel by Brueghel (1563):

And, indirectly, these depictions may not have been entirely mistaken. Many scholars believe that the story of the Tower of Babel may describe the building of a ziggurat, a tower which does not literally ascend into the physical sky, but which ritually allows the priests to ascend the heavens to the presence of the gods in the temple at its top.