This is Part 4 of the series “The Real Elder Price and the Mormon Boys.”

Read Part 1 Part 2 , and Part 3

Disclaimer: Obviously, The Book of Mormon Musical is intended to entertain, not to serve as a primer on Mormonism. This series of essays is offered simply as a view of what missionary life is actually like for Mormon missionaries in Africa, not as a direct response to the musical—though there are a few responses. The missionaries featured in these essays served in the Republic of Congo and Cameroon. The missionaries in the musical are in Uganda. Of course, each African country is distinctive. Nonetheless, for the purposes of this essay, I often refer to Africa as a whole rather than to the specific countries of Cameroon or the Congo.

On June 12, 2010, I sent Elder Chiloba Chirwa an email telling him that I had just received a gift from his mother—a copper plate with the name ZAMBIA on it. Two days later, I got an email from Fiona, Elder Chirwa’s sister: “Jacob has been ill and has passed away today. It is completely devastating, but we are staying strong and know that we will be reunited as a family again.”

On June 12, 2010, I sent Elder Chiloba Chirwa an email telling him that I had just received a gift from his mother—a copper plate with the name ZAMBIA on it. Two days later, I got an email from Fiona, Elder Chirwa’s sister: “Jacob has been ill and has passed away today. It is completely devastating, but we are staying strong and know that we will be reunited as a family again.”

Elder Chirwa had lost his father. I emailed him immediately, starting with the subject line “I already know.”

Now the missionary companions—this “band of brothers”—were called upon to mourn with their friend.

Elder Lisowski described the scene in the missionary apartment:

I found out the same day he did, before he ended up coming home. I tried to make the apartment as comfortable as possible and just figure out how I could help somehow. He came in kind of shell shocked, eventually told us what had happened, and I’ve just spent the past couple of days sitting in his room whenever he’s there. I’m not surprised that you know, either. I actually talked with Chirwa a little bit about it. ‘What do you think Sister Young is thinking right now?’ His response was on the lines of ‘There’s no way she knows.’ So I gave him a look, which in essence said, ‘Sister Young. . . .not knowing something?”

I was amazed at the ways I had been woven into Elder Chirwa’s life, without ever having met him. Regardless of the physical distance between us, we were bound in a relationship which called upon us to care for one another. He was my brother, my son, my friend.

“It’s hard for me to hold back tears right now,” he wrote to me. “We should be grateful for the lives that have touched ours. I am grateful for my father. I was blessed to be his son.”

I have as yet to see any form of artistic manifestation in the church around us. I have always felt that there hasn’t been enough encouragement for the local artist to showcase their talent. One reason for this is the belief inculcated in the people that the only approved art manifestations are the ones coming from Utah. And so we sit to watch videos of conversion stories as our missionaries do their work. This is well and good but I feel that watching a local missionary at work in any outside place would impact our youth.

The fact that Jacob’s own son was serving as a missionary in “an outside place” made his observation poignant and personal. Indeed, Elder Chirwa would make an inspiring subject for a Church video or a film. Having already suffered with malaria and chicken pox, he was now bearing the burden of his father’s death. He acknowledged the challenges with a very Mormon insight on the ways pain catalyzes our personal evolution: “There just seems to be no end to the obstacles on my mission. I can’t help but wonder what the Lord is molding me into.”

I sent Jacob’s interview to Chiloba.

He could have returned to Zambia for the funeral, but elected to remain where he was. He sent these words to be read at the memorial service:

I am realizing quickly that the comfort of the Spirit is not only a voice telling you all will be all right, but it is a deep, even limitless understanding of eternal truths. The Spirit tells to trust in the knowledge of God, giving us understanding of His omniscience. It also helps us understand the time-defying state of forever—that perspective which we call Eternal. In this comforting scope of understanding, death is a mere temporal separation…I love you all. I am with you in spirit. I love my father and all he was and did. Let us remember him, let our hearts not be broken but filled with love and appreciation for Jacob Chirwa. Let us remember that God’s grace is sufficient for us –He will see us through.

Just over a year later, my own father appeared to be dying. He had already been on dialysis for three years, and was now bleeding internally. When the doctors stopped the bleeding, Dad had heart attacks. When they prevented the attacks, his bleeding worsened. It appeared that we were in a catch 22 which would end his life.

I continued to communicate with Elder Chirwa, who was now in the final stretch of his mission. Though he was half my age, I knew he understood what I was going through in a way the others in the “band of brothers” couldn’t.

“You were there for me,” he wrote, “and I will be there for you.”

I poured my heart out to this young man I had never met, this remarkable missionary who I had so grossly underestimated when first introduced to his name. How I loved him! I wrote: “This process of losing my father—and I don’t know how long it will take—is so much harder than I ever imagined it would be. I wish we didn’t have this one thing in common, but it helps to know that you know.”

In reply, he sent me the lyrics to a country song:

And when you dream, dream big

As big as the ocean blue

‘Cause when you dream it might come true

When you dream, dream big

“Sister Young, dream big,” he added. “The plan of our Heavenly Father is greater than we can understand.

Today I received a birthday card that Dad had gotten me but never got to sign. My aunt found it in his diary. I was happy. My aunt said that Dad would have loved to give me the keys to the world.

Despite him not being there to do so, I have a Heavenly Father that surely will.”

There would be yet another surprise amongst Jacob Chirwa’s papers: a poem he had written prophesying his own death, as though he had dreamed it.

The funeral cortege is long,

longer than any that I have ever seen…

All I know is that before I was placed here

There was a large crowd of people wailing

As they passed by me.

I must confess

I have never seen such ugly and contorted faces in my life

Faces all screwed up

As if they had been forced to swallow an overdose

Of quinine tablets without water,

All howling at the top of their voices,

Calling my name…

There were a lot of people

peeping into the coffin where my body lay in state.

I even saw what would have been

A beautiful girl

if her face was not contorted.

She peeped and I think she smiled, and was gone…

And so it continued,

This long line of people walking past and mumbling.

At one point, I almost burst out laughing

when one of them said,

What a handsome face!

I thought to myself,

What, me—handsome

Actually, I am ugly.

The ugliness that makes the owner aware of it.

Everything on my face is a sort of

culmination of God’s craziest adventures in creativity…

So you now understand my amazement

when this person mentioned

My being handsome.

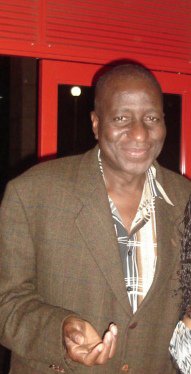

Had Jacob Chirwa considered himself ugly? Was he genuinely surprised that someone would think him handsome? Certainly, he was admired in Zambia. His wife reported that he was renowned not only as an actor but as an expert on Isaiah. His sister-in-law said that just days before his death, he had taught a beautiful Sunday school lesson, using his acting abilities to their fullest, completely comfortable with his class. And yet there were his own words—the suggestion that he did not recognize that he was handsome.

Jacob’s poem reminded me of some plot points in the musical Man of La Mancha, based on Cervantes’ Don Quixote. An old man, who appears delusional, imagines that he is actually a knight and must do good and worthy things to earn a noble title. Ultimately, he fights a giant (really a windmill) and demands that a barber give him a title. The barber puts his shaving basin on Don Quixote’s head and dubs him “Knight of the Woeful Countenance.” Thus ennobled, Don Quixote seeks a virtuous woman to whom he will dedicate all of his battle victories. He selects a prostitute/scullery maid as the object of his affection—imagining her out of her rags and into resplendency. Ultimately, she is changed by the way he sees and treats her. Her eyes are opened to her own glory. Later, when Don Quixote is forgetting his own quest, she begs him to remember what he had stood for: the impossible dream. (“To dream the impossible dream/ to fight the unbeatable foe/ to bear with unbearable sorrow/ to run where the brave dare not go…”) Just as he had awakened her to a sense of something greater than she had dared imagine, so she awakens him to a remembrance of his own nobility. Even if his dreams have been “impossible,” his heart has been good, and he has lifted the downtrodden by treating them with dignity.

There is an ‘impossible dream” in The Book of Mormon Musical, too, though not an inspiring one. In fact, it’s quite the opposite of the Quixotic illusion. “Spooky Mormon Hell dream” shows the missionaries encumbered by their own and others’ absurd expectations, laden with shame, supposing they have been revealed as “unworthy” and then tormented by medieval devils, who come complete with horns and pitchforks. (Devils in real Mormonism are much more subtle and sly.)

Of course, as good satirists, Parker and Stone have identified the Mormon proclivity towards guilt as a fruitful subject for humor. In “Spooky Mormon Hell Dream,” the missionaries are haunted by memories of petty misdeeds from their childhoods, and dream that Jesus hates them and denounces them with a vulgar epithet. Tyrannical fathers rise from the sludge of memory to ground them for stealing donuts—or breaking one of several hundred missionary rules.

As in the song “I Believe,” where there is no hierarchy of central and subordinate/irrelevant/false doctrine, in the Hell dream, there is no hierarchy of misdeeds. In this dream, stealing a donut and them blaming it on your brother is tantamount to committing genocide in Nazi Germany.

In Mormonism as we actually live it, things are far more complex and full of promise. We do burden ourselves with guilt, but we are not unique in that. More important is the fact that we really do undertake impossible dreams—such as making missionaries of teenagers and sending them to places like Africa. In the best of times, and when we are living our religion, our dreams are magnificent and overflowing with love and compassion—including towards ourselves. And often (more often than we recognize), those dreams come true.

Chiloba Chirwa, a knight of radiant countenance, dreamed big, and had sweet memories of the father he would never see again in mortality. “Before my mission, I overheard a telephone conversation between my dad and mum,” he said. “She asked if him if he felt I should go on my mission, and he replied ‘I think he has done well enough to go’. I always knew that he supported what I was doing.”

I had a dream once that I was about to meet Chiloba Chirwa. He was just turning to look at me, and then disappeared as I awoke. But though I have never met him, I have heard from those who know him well that no photograph does him justice. He (no doubt like his father) is far more handsome than a camera can reveal.

Miraculously, my father survived the crisis and lived to celebrate his eightieth birthday with his family. All of my siblings had flown in for this, uncertain if we would be eating a birthday cake or planning a funeral. At 2:00 p.m. on his birthday, supported by two of his sons, Dad walked into his own home.

I was not yet called upon to endure the loss of my father, as Chiloba had done. But the realization that I had “been there” for him—that I had been alerted to his loss so that my words were waiting when he was able to access a computer; that I had interviewed Jacob before he died and thus could give Chiloba his father’s own words; that I had met Chiloba’s mother and sister—appeared miraculous.

As so often happens, we find ourselves at the intersections of each other’s lives at just the right moment, tooled in ways we had not heretofore understood. We become angels for one another. That’s the real Mormon dream.